A Deeper Look: Getting To Know Different Cultures

Last week we gave you an overview of the basic strategies for cross-cultural management, including a few possible ways to create inclusion for international students, build a community and make life on campus generally more rewarding as well as enjoyable.

However, cross-cultural management for international students can only work if you are more than simply familiar with different cultures and their peculiarities.

A model of culture classification

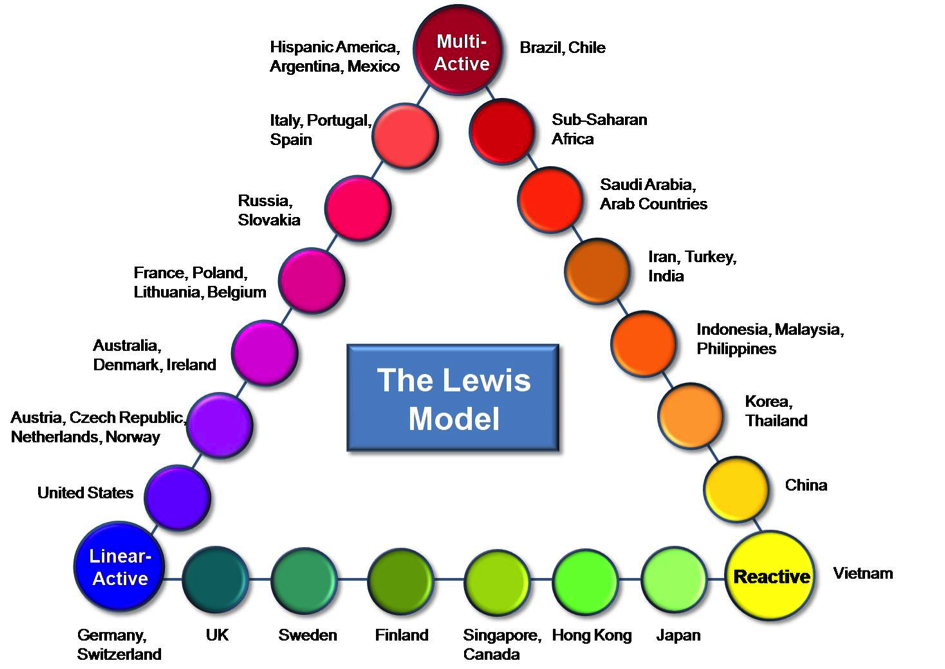

In the upcoming days, we will introduce you to a model of culture classification that divides cultures into three big groups – linear-active, multi-active and reactive. This is the model of distinguished linguist and one of the most celebrated cross-cultural management theorists of our time – Richard D. Lewis. He developed and discussed it in detail in his seminal publication, “When Cultures Collide“.

The book argues that categorizing countries according to their geographical position, political preference or religious tradition is not accurate. After all, Christians in Nigeria might be not so similar to Christians in Russia; Cuba is nothing like Mexico and Egyptian democracy differs significantly from that in Australia.

With this in mind, Lewis introduces a culture typology that sorts countries mostly using criteria such as work ethics and communication preferences.

Three types of cultures

Thus, each group displays particular features that together create a unique cultural background. More often than not, representatives of the same country share common features that are distinctive of this country’s cultural type.

For example, people from Linear-active countries are focusing on plans and schedules. They are caring mostly about getting the results in a step-by-step way. Also, they are open, friendly and focused. Typical examples of linear-active countries are Germany and the U.S.

Multi-active country representatives care mostly about people and processes. Their behaviour is very different from that displayed by linear-active people. They can adapt very easily to different situation and changing circumstances and can also work on several different activities at the same time. Italy, Saudi Arabia or Bolivia are great examples of multi-active countries.

Reactive cultures are the most introverted of all types. The usual characteristics of the reactive type include more listening than speaking, being respectful, avoiding conflict and trying to reach a diplomatic agreement where everyone wins. Lewis states that Japan, China and Vietnam are the most typical examples of reactive cultures.

See more features associated with each cultural type in the table below:

Common traits of Linear-Active, Multi-Active and Reactive categories (p. 32 “When Cultures Collide”, Richard D. Lewis)

Avoid having stereotypes

Not every single person from Switzerland is keeping up with timetables, just like not every Greek is choosing to show a lot of emotions. What we offer here is a general picture that would allow us to understand better and more easily a wider variety of cultures. In this way, we will be able to offer a more welcoming and understanding response to all of them.

It is worth mentioning that this model doesn’t use the form of a scale, but the form of a triangle. A country inside the triangle can be very reactive, quite multi-active or just a bit linear-active. We measure the exact amount of each feature only in comparison to other countries:

The Lewis Cultural Types Model (p.42 “When Cultures Collide”, Richard D. Lewis)

Applying culture classification to international student contexts

As an educator, you should look into this system as a thought-invoking, inspiring and, hopefully, useful tool. Following it blindly could bring a lot of misunderstandings with international students. And yet, we think that this model is very informative and can indeed be very helpful.

What is your experience with observing international students coming from more similar or more different cultures? Do you notice any patterns and trends?

Let us know in the comments below!

I saw Dr Lewis speak, and I must say I found his concept to be incredibly reductive and his manner was often offensive.

He made the point that a respondent from Paraguay was placed towards the “reactive” corner of the triangle, due the fact his ancestors had presumably migrated from the Asian continent over 10,000 years ago. Supposedly, this meant that he had inherited the traits Dr Lewis banally attributes to “Asians”. Linking personality traits to circumstances and the cultural environment is one thing, but implying that one’s genetics or ethnic heritage is indicative of one’s behaviour or psychology is quite frankly dangerous and absurd.

Dr Lewis went into great detail about the behaviour of Italians, in contrast to Germans: the emotional, passionate and impulsive, versus the logical, calculating and humourless. In light of his equating genetics with behaviour, I wonder how he would explain the alleged behaviours of peoples from those regions a few thousand years ago – the ancient Romans were known for being orderly and the germanic tribes were the “fiery barbarians”.

It seems to me that there is no way that a mere 150,000 completed online surveys (across 68 countries, mind you!) could possibly lead to the conclusions drawn. Least of all, that this would be a reliable sample. Instead, I think these are the outdated observations of a well-travelled businessman.

Some of the points he makes may hit the mark for those seeking to learn the communication and etiquette to do business in a Japanese boardroom, but there is not much original thought here. Aristotle and Montesquieu did it first, see the latter’s (even more outdated!) theory on climate anthropology.

At best, Dr Lewis’ presentation was interesting and mildly entertaining, if not just for the tone-deaf generalisations and anecdotes. At worst, his theory is pseudoscientific with no place in today’s multicultural & globalised world.